Scope 3 Calculation Mistakes That Inflate Your Carbon Footprint

- C² Team

- 3 minutes ago

- 8 min read

Most companies report Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions with reasonable confidence. The data sources are internal, the boundaries are clear, and the calculation is relatively straightforward. But Scope 3 — the emissions that live across your entire value chain, from raw material suppliers to the end-users of your products — is a different story entirely.

Scope 3 can account for up to 90% of a company's total greenhouse gas footprint. Yet it remains the most inaccurately reported category in corporate sustainability disclosures. The errors aren't always deliberate. They're a product of data gaps, methodological shortcuts, unclear boundaries, and — most commonly — a fundamental misunderstanding of what Scope 3 calculation is actually for.

These mistakes don't just inflate your numbers. They mislead your investors, misrepresent your supply chain risks, and make your decarbonization strategy impossible to prioritize correctly. Here are the seven most consequential Scope 3 calculation mistakes we see — and what to do instead.

Mistake #1: Using Spend-Based Data When Activity Data Is Available

Spend-based estimation has its place. When you have no access to supplier data and need a rough starting point, multiplying your spend by an economic emission factor gets you into the ballpark. The problem is when companies use this method not as a temporary placeholder but as their primary calculation approach — even when better data is within reach.

When you calculate supplier emissions based purely on money spent rather than actual physical activity — tonnes of material purchased, kilometres transported, kilowatt-hours consumed — your numbers can be off by a factor of two to five. For capital-intensive categories like raw materials, upstream manufacturing, and logistics, the variance is even wider. Two suppliers receiving the same payment can have emission profiles that differ by an order of magnitude depending on their energy source, production technology, and operational efficiency. Spend-based methods erase all of that nuance.

The result is a Scope 3 inventory that looks precise and complete on the surface but has almost no relationship to the physical reality of your supply chain.

What to do instead: Prioritize activity-based data wherever it is available. Work with suppliers to collect actual quantities — material weights, energy bills, freight volumes — and apply appropriate emission factors to that activity data. Reserve spend-based estimation only for low-materiality categories where primary data collection is genuinely not feasible.

Mistake #2: Double Counting Across Categories

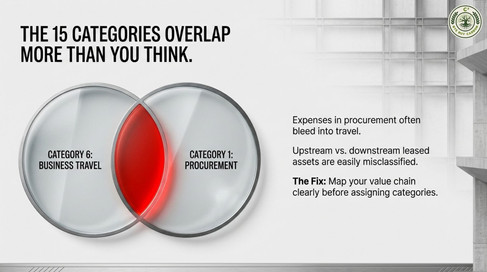

The GHG Protocol defines 15 Scope 3 categories, and they overlap more than most sustainability teams anticipate. Without clear internal boundaries, the same emission source can end up counted in two — or more — categories simultaneously, inflating your total footprint and distorting where your hotspots actually sit.

Some of the most common double-counting scenarios: business travel expenses processed through a travel management company appearing in both Category 6 (Business Travel) and Category 1 (Purchased Goods and Services); fuel and energy-related activities from Category 3 bleeding into Categories 1 and 4 when boundary definitions are loose; upstream leased assets being counted under both Category 8 and Scope 1 depending on which operational boundary the team chose to apply.

These aren't edge cases. They happen regularly, particularly in organizations where Scope 3 data collection is spread across multiple teams — procurement, finance, facilities, logistics — who aren't coordinating on methodology.

What to do instead: Before any data collection begins, build a detailed value chain map that assigns every emission source to exactly one category. Write down the boundary rules. When a source could plausibly sit in two categories, make a documented decision and apply it consistently. Methodology transparency isn't just good practice — it's what allows your numbers to hold up under third-party verification.

Mistake #3: Stopping at Tier 1 Suppliers

Engaging your direct suppliers for emissions data is already a significant operational challenge. It's understandable that most companies stop there. But the highest-carbon activities in a value chain frequently sit two or three tiers back — at the raw material extraction, primary processing, and upstream energy generation stages that your Tier 1 suppliers buy from, not what they sell to you.

A textile company that calculates emissions only from its fabric suppliers misses the cotton farming, irrigation, chemical dyeing, and yarn spinning stages that are responsible for a large share of the industry's footprint. An electronics manufacturer that stops at component suppliers ignores the mining, smelting, and refining of rare earth metals that power those components. A food and beverage company that only measures its ingredient suppliers' direct emissions misses the upstream agricultural inputs — fertilizers, pesticides, water — that drive most of the lifecycle impact.

Stopping at Tier 1 is not the same as measuring Scope 3. It is measuring a small, often unrepresentative fraction of it.

What to do instead: Build a supplier engagement program that is designed to cascade beyond Tier 1. For your highest-materiality spend categories, identify the most significant Tier 2 and Tier 3 nodes and work toward data collection or credible secondary data estimates for those tiers. Even a rough but informed picture of Tier 2 emissions is more useful for decision-making than a precise but incomplete Tier 1 inventory.

Mistake #4: Using Global Average Emission Factors for Local Contexts

Emission factors are not interchangeable. A global average grid emission factor for electricity may be acceptable as a last resort, but applying it uniformly across a value chain where suppliers operate in vastly different geographies and grid conditions introduces errors that compound across every affected category.

India's grid emission factor, for example, varies significantly across states and distribution zones. A supplier running operations on renewable energy in Tamil Nadu has a radically different electricity emission profile than one drawing from a coal-intensive grid elsewhere. Using the same national average for both makes your numbers wrong in both directions simultaneously. The same principle applies to transportation emission factors — road versus rail, diesel grade, load factor — as well as manufacturing processes, where technology vintage and fuel mix can vary widely even within the same sector and geography.

This mistake is particularly costly for companies with complex, multi-geography supply chains. The more diverse your supplier base, the more your use of global averages diverges from reality.

What to do instead: Use the most geographically and technologically specific emission factors available for each activity. In India, refer to the Central Electricity Authority's latest state-wise grid emission factors. For materials and manufacturing, use process-specific data from recognized databases such as ecoinvent or EXIOBASE. Where primary supplier data is available, use it over any secondary factor.

Mistake #5: Omitting End-of-Life Treatment (Category 12)

Category 12 — End-of-Life Treatment of Sold Products — is one of the most consistently underreported Scope 3 categories. Companies often skip it entirely, reasoning that what happens to their products after they leave the factory gate is outside their control and therefore outside their responsibility. Under the GHG Protocol, this reasoning is incorrect.

The emissions associated with how your product is ultimately disposed of — whether it goes to landfill, is incinerated, is recycled, or is composted — are allocated to the company that produced and sold that product. For businesses in packaging, FMCG, consumer electronics, construction materials, textiles, and any other sector producing physical goods with significant end-of-life emissions, omitting Category 12 can understate total Scope 3 emissions by 10 to 30 percent. For companies producing single-use plastics, non-recyclable packaging, or products with high landfill methane potential, the gap is larger.

What to do instead: Model realistic end-of-life scenarios using national or regional waste treatment statistics. Identify the likely disposal pathways for each product in your portfolio — what percentage goes to landfill, what is recycled, what is incinerated — and apply the appropriate waste treatment emission factors. If your company has circular economy goals, Category 12 data is not just a compliance requirement. It is the baseline that makes your progress measurable.

Mistake #6: Not Updating Base Year Data After Structural Changes

A base year provides the benchmark against which all future emissions reductions are measured. It is only meaningful, however, if it accurately reflects the organizational and operational boundaries it was calculated for. When companies undergo major structural changes — acquisitions, divestitures, outsourcing shifts, major supplier transitions, product portfolio redesigns — and fail to recalculate their base year accordingly, every subsequent comparison is built on a false foundation.

A company that acquires a high-emission subsidiary after its base year was set will appear to have dramatically increased its emissions, even if operational performance improved across the entire business. Conversely, a company that divests a heavy industrial division will appear to have made impressive reductions that have nothing to do with actual decarbonization efforts. Both distortions make it impossible to credibly measure progress.

There is also a subtler version of this mistake: companies that set ambitious reduction targets against a base year that was itself inflated due to the calculation errors described in this article. Their reduction trajectory looks impressive. Actual emissions remain flat.

What to do instead: Establish a formal base year recalculation policy with clearly defined triggers. The GHG Protocol recommends recalculation whenever a structural change results in a significant difference in base year emissions — typically defined as greater than five percent of total. Apply this policy consistently, document all recalculations transparently, and communicate the reasons for any base year revision in your public disclosures.

Mistake #7: Treating Scope 3 as a Reporting Exercise Rather Than a Strategic Tool

This is the most consequential mistake on the list — and the one that makes all the others worse. When Scope 3 calculation is driven by a disclosure deadline rather than genuine business intent, the entire exercise is optimized for the wrong outcome. Data quality is treated as good enough rather than as good as possible. Hotspots are identified in the inventory but never acted upon. Supplier engagement is shallow, one-time, and ceremonial. The final number gets filed in an annual report, and nothing changes.

This approach is increasingly unsustainable — not just environmentally, but commercially and regulatorily. BRSR Core is now mandatory for India's top 150 listed companies. CSRD is extending its reach across European value chains, which means international suppliers to European companies face growing data requests. SBTi requires credible Scope 3 targets as a prerequisite for net-zero validation. CDP scoring increasingly rewards depth of Scope 3 engagement. The regulatory and reputational stakes for companies that have treated Scope 3 as a checkbox are rising fast.

What to do instead: Treat your Scope 3 inventory as the primary input to your decarbonization strategy. Use the data to identify where in the value chain interventions will have the highest impact per rupee spent. Use it to prioritize which supplier relationships need to evolve and which product design decisions carry the highest lifecycle carbon cost. Use it to set credible, science-aligned reduction targets. Scope 3 data is your roadmap to meaningful climate action. The only mistake bigger than calculating it wrong is not using it at all.

The Bottom Line

Getting Scope 3 right is not just a technical exercise. It is a credibility exercise, a strategy exercise, and — increasingly — a regulatory compliance exercise. The seven mistakes described above are all fixable. None of them require unlimited resources or perfect data. They require methodological rigor, cross-functional coordination, supplier engagement commitment, and a genuine organizational intent to understand and reduce value chain emissions.

If your Scope 3 numbers feel uncertain, that is a signal. The question is whether you act on it before your investors, auditors, or regulators do.

Csquare (C²) is a carbon intelligence platform helping companies build accurate, audit-ready emissions inventories and translate data into actionable decarbonization strategy.

👉 Connect with C² (Csquare) to get started! 🌐 www.csquarecarbon.com ✉️ info@csquare.co.in

Comments